After the Meiji Restoration, with the enforcement of the Sword Abolishment Edict (Haitōrei), martial arts in Japan experienced a sharp decline. Society's values became entirely Westernized, and disciplines like kenjutsu were viewed as outdated remnants of the feudal era.

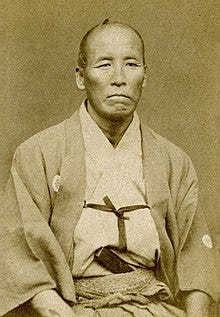

Amid this backdrop, one master rose to support impoverished samurai and preserve the endangered techniques: Sakakibara Kenkichi (榊原鍵吉) of the Jikishinkage-ryū (直心影流). Inspired by sumo exhibitions, he introduced the "Gekiken Kōgyō" (撃剣興行), or fencing exhibitions, which gained significant popularity. However, this was not a long-term solution, and kenjutsu appeared destined to continue its decline.

Gekiken (撃剣), meaning "sword fighting" or "sword combat," was a form of training and competition with swords that emerged during the Edo period but gained greater prominence in the Meiji era.

Unlike traditional kenjutsu (剣術), which focused on formal techniques and kata, gekiken allowed for free sparring between practitioners using shinai (bamboo swords) and bōgu (protective armor). This approach fostered a more dynamic and safer style of engagement.

However, in the 10th year of the Meiji era (1877), the Satsuma Rebellion broke out, during which government troops struggled to counter the sword-wielding samurai of Kagoshima. In response, the Tokyo Metropolitan Police formed a special unit of swordsmen, the "Keishichō Battōtai" (警視庁抜刀隊), comprised of samurai highly skilled in kenjutsu. This unit successfully subdued the Satsuma samurai, once again highlighting the value of kenjutsu.

Later, during the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars, a wave of nationalism arose. Efforts began to unify Japanese martial arts, which had previously existed in isolation within individual dōjō or regions, as part of the national culture. As a result, on April 17, 1895 (Meiji 28), the Dai Nihon Butoku Kai (大日本武徳会) was established as the central organization for martial arts. Kenjutsu transitioned from being merely a "technique" (jutsu) to being recognized as a "way" (dō) that contributed to the development of human character. The term "kendō" (剣道) began to emerge to reflect this new perspective.

In this context, the Metropolitan Police and the Butoku Kai standardized kenjutsu techniques, which previously varied widely among schools, establishing universal rules and methods for shinai-geiko (bamboo sword sparring). Although the origins of shinai-geiko date back to dōjō practices in the mid-Edo period, the modern structure of kendō was solidified during this time.

The Butoku Kai, while promoting the preservation of traditional martial arts, also encouraged the dissemination and unification of kendō, laying the foundation for its modern form. However, before World War II, many kendō practitioners identified themselves by their school's name during competitions. They worked to preserve the techniques of their own styles while coexisting with other schools through the shared practice of kendō.

In the 1890s, kendō clubs began to emerge at universities such as Tokyo Imperial University and Keio University, contributing to the growth of kendō as a team activity. The student mindset of freedom and equality led to the development of a refereeing system similar to what exists today, and a more sport-oriented approach was adopted. This differed from the strict kenjutsu of traditional dōjō, helping to popularize kendō.

In 1912, the Butoku Kai established the "Dai Nihon Teikoku Kendō Kata" (大日本帝国剣道形), and kendō was introduced into the educational system as part of physical education. Specifically, in July 1911, the Ministry of Education decided to add judo and kendō to the curriculum of secondary schools. From the Shōwa era onward, kendō developed significantly, becoming a type of national competition as popular as baseball.

However, with the onset of the Pacific War, martial arts were incorporated into military education, and the Butoku Kai became a government institution, marking the end of its history with the conclusion of the war.

After the war, during Japan's occupation, kendō was banned from the educational system along with other martial arts, plunging them into another period of decline. Kendō, in particular, faced harsh criticism from the occupying forces and was only permitted to resume in 1950 under the name "shinai kyōgi" (撓競技). However, the full practice of kendō was not restored until after the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1953.

In the post-war period, kendō re-emerged as a democratic sport, distancing itself from the pre-war martial arts mentality. As a result, certain martial aspects of the practice were intentionally limited.