The first swords (刀剣) used by the Japanese were not, of course, the nihontō (日本刀) we know today. Instead, they were stone, bronze, and iron swords unearthed from archaeological sites dating back to the Jōmon and Yayoi periods. Among the various weapons crafted from different materials, iron swords eventually surpassed others in popularity due to their high combat effectiveness.

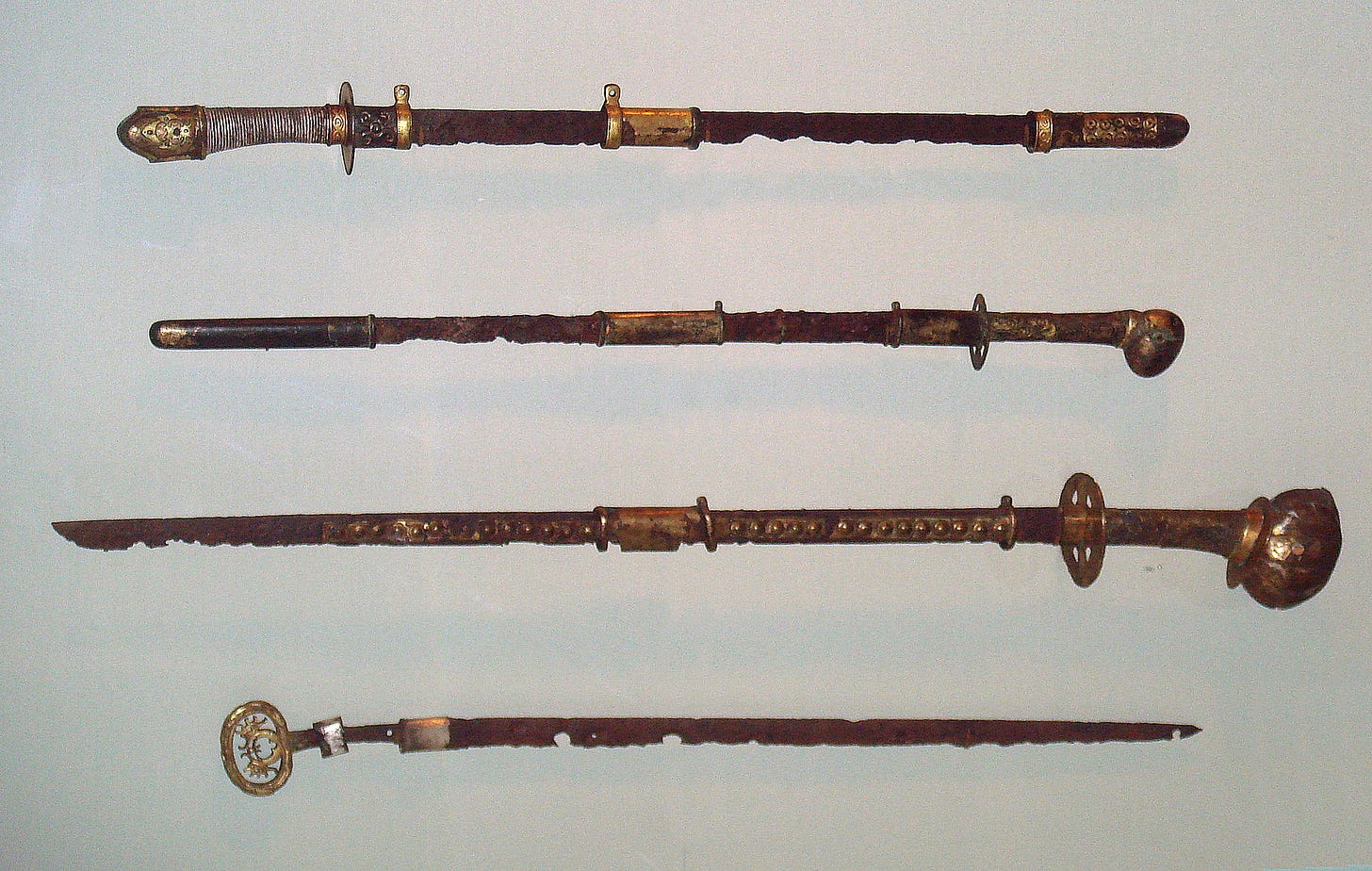

For a long time, single-edged or double-edged straight swords were the most common. From double-edged swords influenced by the large ringed swords (kantō-tachi) from the continent to single-edged and straight-edged swords excavated from periods spanning the Kofun to the Nara and Asuka eras, it is believed that the swordsmanship techniques of that time focused on the handling of these straight swords. However, the kenjutsu techniques of ancient times have not been passed down in documented form, so it is unclear how these straight swords were used exactly. Furthermore, ancient times were an era dominated by battles fought in formation, with infantry primarily relying on weapons like the bow and arrow. The sword was mainly regarded as a self-defense weapon for those of high rank. While there may have been techniques to wield it, it is likely that these were not developed on a wide scale.

The use of the Tachi as a complementary weapon to the Bow

The form of the nihontō (Japanese sword) as we know it today developed in the middle of the Heian period (794 to 1185). This was a time when the samurai began to consolidate their power, bringing about a significant shift in combat methods. One of these changes was the transition from foot battles to mounted combat. In the Bandō region (now the Kantō region and beyond to the north), there were numerous breeding grounds for high-quality horses. Samurai, entrusted with managing lands in the east by the aristocrats in the capital and expanding their own territories, settled in Bandō. The horse became an everyday means of transportation and, eventually, an essential tool for combat.

As the saying goes, "the way of the bow and horse" (yumiba no michi), the main weapon in mounted combat was the bow. The skill of handling the bow on horseback, known as kyūba-jutsu (the art of bow and horse), became one of the most important arts of the samurai.

The Ogasawara-ryū school of archery, which still exists today, emerged as a family dedicated to preserving samurai customs (yumiba kojitsu), archery, equestrianism, and etiquette. It is said that the founder of this school, Ogasawara Nagakiyo, served as a master of ceremony and etiquette (kyūhō) for Minamoto no Yoritomo, indicating that kyūba-jutsu schools already existed during the Kamakura period.

The battles of the Heian and Kamakura periods, as described in various war chronicles, show that warriors primarily relied on kyūba-jutsu, while the tachi (cavalry sword) was used in specific situations: when arrows were depleted or when the opponent challenged them to hand-to-hand combat. The tachi, with its pronounced curvature and tip-sharpened blade, had a center of gravity close to the handle, making it easier to wield single-handedly from the unstable position on horseback. Its shape was ideal for sweeping cuts that took advantage of the horse's speed. Although it couldn’t be considered formal swordsmanship, there was an expression, "tachikiri" (cutting with the tachi). However, as the tachi served as a complementary weapon to the bow, it had not yet developed into a complex combat system.